Habronemiasis is also referred to as Habronematidosis in some articles and text books. Of the 12 species of Habronema known to infect mammals there are 3 species that infect horses, donkeys, mules and zebras:

- Habronema muscae

- Habronema microstoma (majus)

- Draschia (Habronema) megastoma

The parasites are known for their ability to produce cutaneous nodules in adult horses. Unlike stomach bots, which are flies, Habronema parasites are spiruroid nematodes. The confusion is caused by the role of flies in the transmission of Habronema species.

Habronema muscae can be found in many regions of the world, but mostly in tropical and sub-tropical regions. They also have moderate prevalence in temperate climatic zones. Draschia megastoma is less common, although it is frequently found in horses in Australia and the USA.

Life cycle

The adult and larval parasites live in the stomach, where they cause no to little impact on health, with some rare exceptions. The parasites live freely in the stomach or in nodules in the gastric fundus, around the pylorus, or near the margo plicatus. Of the three species, Draschia megastoma is the one most often associated with gastric wall nodules.

The adult female H. muscae are longer than the males, measuring 15-35 mm in length. They are white. Draschia megastoma adults are shorter, around 7-13 mm long.

After mating, the adult females in the stomach release larvated eggs, which hatch within the intestine or in the faeces after passage. These small first stage larvae (L1) can survive for up to 7 days in the right environmental conditions. Habronema larvae or larvated eggs are then consumed fly (muscid) larvae that have developed in the manure.

The primary vector of Habronema muscae is Musca domestica (common housefly), and the vector of Habronema microstoma is Stomoxys calcitrans (stable fly). The primary fly vector of Draschia has not been determined. After consumption, both larvae develop together. Around 7 days after consumption Habronema moult to second phase larvae (L2). Third stage Habronema (L3) larvae are found in mature pupae or young adult flies, and 48 hours after their moult they reach the head of the fly.

The flies deposit the L3 Habronema larvae around the lips, the horse swallows the larvae and end up in the stomach and mature as adults – and the cycle is complete.

The problems arise when the flies deposit larvae in other areas over the horse, such as around the eyes, face, genital mucosa, or other sites on the body, particularly in areas of broken skin. On rare occasions the L3 larvae can reach internal body organs, such as the liver, lung or brain. The larvae in these sites have arrested development, that is, they do not develop into mature adults.

As the name suggests in temperate zones the frequency of infection increases over summer, coinciding with the increase in fly numbers.

Response to L3 larvae

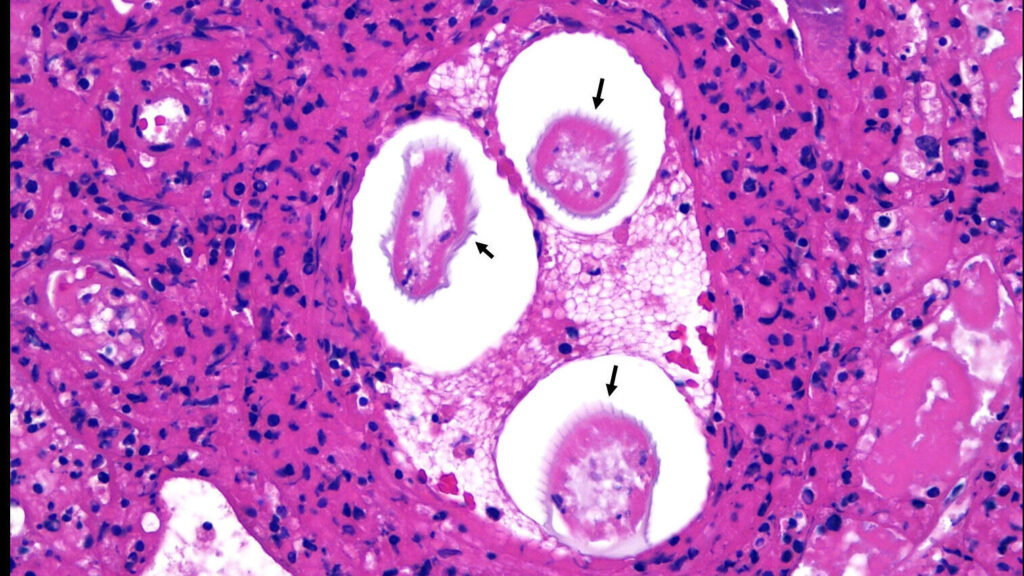

Within the gastric mucosa Draschia megastoma (most commonly) can induce a nodular response, characterized by granulomatous lesion with central necrosis and an influx of eosinophils.

The cutaneous response is characterized as a hypersensitivty reaction to the aberrant larvae.

Signs of infection

The disease is seasonal, beginning in spring, peaking in summer, and then regressing in autumn and winter. The medial canthus of the eye is a common site, as is behind the commissure of the lips. The legs are also commonly involved, as is around male genitalia, particularly the urethral process.

Typically only single animals within a herd are affected, and some horses appear to be predisposed to developing cutaneous lesions. Often these individuals will develop lesions yearly.

Classically, the lesions are granulation tissue that contain small (1 mm diameter), gritty yellow granules. These are necrotic foci that surrounds the aberrant larvae. In some cases the lesions will be nodules that have not ulcerated.

Diagnosis

The suspicion of Habronema infection is based heavily on the season and the clinical appearance of the lesions.

The larvated eggs or larvae are typically not detected using standard faecal flotation methods. Even the Baermann technique used to detect larvae has a low sensitivity, even in the face of high loads.

The diagnosis is definitively established using histopathology of a biopsy of lesion tissue. This includes the presence of eosinophils, granulation tissue and parasite larvae.

There are a number of other diseases to consider based on appearance of lesion, including proud flesh (exuberant granulation tissue), fibroblastic sarcoids, neoplasia (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma), and fungal granulomas.

Treatment and Control

- Reduce/eliminate the larvae using a systemic oral macrocyclic lactone (ivermectin, abamectin, or moxidectin). Some have recommended a second dose 3 weeks later.

- Treat the hypersensitivity reaction using intralesional corticosteroids (triamcinolone, 5-15 mg/lesion, up to 20 mg total dose per horse). Oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg PO) is not as effective, but may help.

- Fly control to prevent further infection. Cover any skin breakage/wounds.

Topical medications have been advocated as well, including topical steroids, DMSO, and ivermectin. It is difficult to draw conclusions about topical therapies, as the data just isn’t there. Be careful with DMSO, as it will carry accompanying drugs systemically into the horse.

The use of macrocyclic lactones over summer is recommended in susceptible horses, but this will not guarantee that lesions will not develop.

There are some veterinarians concerned about Habronema species resistance to macrocyclic lactones. Although there are no data to support this, it serves as a reminder to be judicious when using these products on your horses.

Tags: Parasites, Dermatology