Annual Ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) is seen most commonly in WA over the summer months with the feeding of contaminated hay. Ingestion of contaminated pasture or hay results in an acute and often fatal disease of livestock.

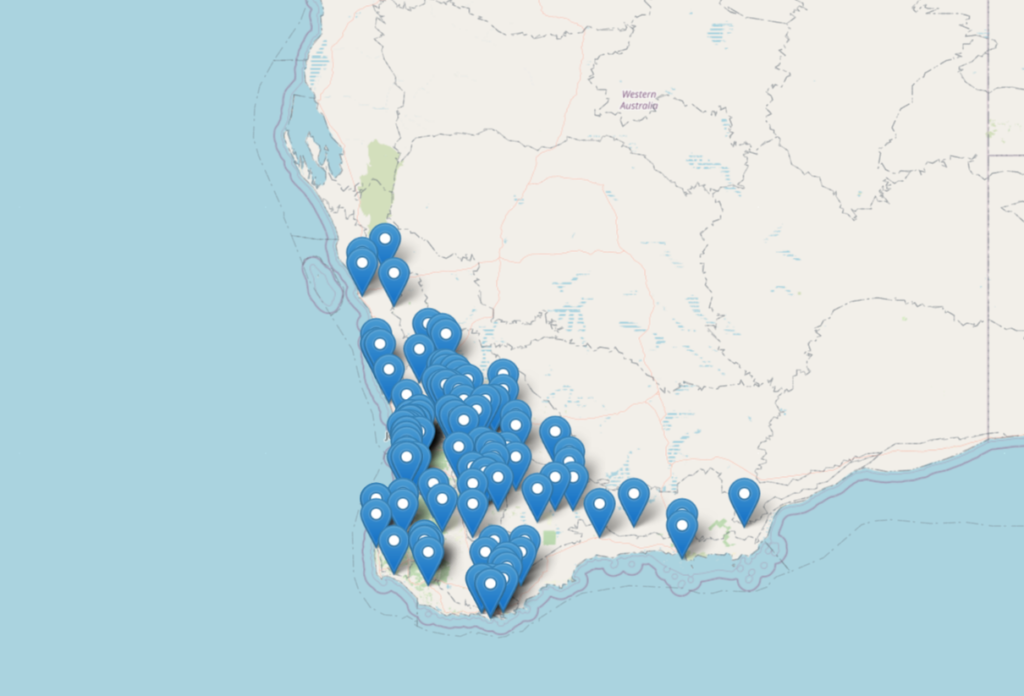

Originally the condition was seen from hay grown in the WA wheatbelt but this has spread to other regions (coastal and southern) over the past decades. The disease is caused by bacterial toxins from the organism Rathayibacter toxicus. This bacterium is carried by and transmitted by a parasite, specifically Aguina species (most commonly Anguina funesta), a nematode that lives in the developing seed heads of some annual grasses. Several different grass species can be involved including Lolium, Polypogon, and Agrostis, but the disease is primarily associated with annual Wimmera ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin) in South Australia and Western Australia. Wimmera ryegrass is a very common grass of south western WA (see map below). The species originated in the Mediterranean region and was introduced into Australia as a pasture species. It is now naturalised in all states and territories of Australia. It does well in sandy soils and has some salt tolerance. Consequently, it is not uncommon to find Wimmera ryegrass in meadow hay and occasionally as a contaminant in other hays.

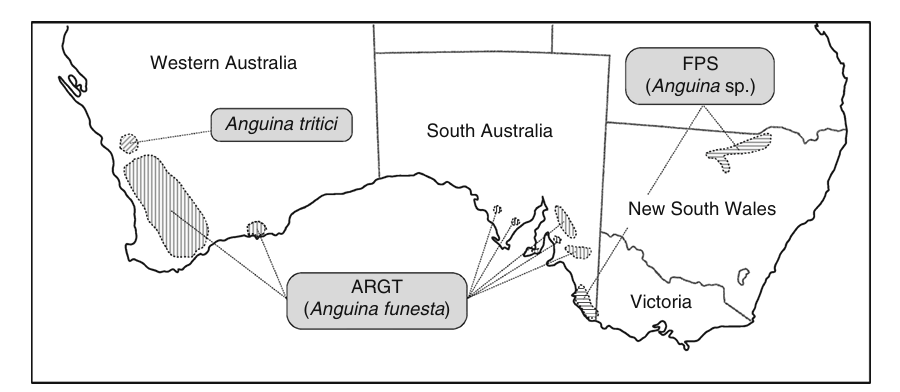

Annual Ryegrass Toxicity has been reported in Western Australia, South Australia and South Africa. First described in Western Australia in 1968 in the Gnowangerup region the disease is now widespread and continuing to spread.

The plant-nematode-bacteria lifecycle

Rathayibacter toxicus was formerly known as Clavibacter toxicus, and later as Corynebacterium rathayi. This Gram-positive actinomycete bacterium is transmitted by seed gall nematodes (Anguina sp., including Anguina funesta).

The distribution of ARGT is linked to the presence of the Anguina nematodes.

Other Anguina species, also associated with harboring the bacterium R. toxicus, are responsible for the conditions known as Flood Plain Staggers and Stewarts Range Syndrome. This is seen in livestock grazing infected Agrostis avenacea (blown or blown away grass) and Polypogon monspeliensus (annual beard grass), respectively. Flood plain staggers is associated with the death of horses, cattle and sheep in the flood plains of the Darling river in northern New South Wales. Stewart Range Syndrome occurs in the flood-prone regions of southeast South Australia. The syndrome may also occur in US (specifically Oregon) associated with fescue grasses.

As part of the parasite life cycle the second-stage juveniles of Anguina funesta become anhydrobiotic. Anhydrobiosis is a dormant state where water is lost and the dessicated parasite survives as galls with little or no metabolism until sufficient rains arrive. Both the nematode and bacterial galls can persist in extreme environments for decades until adequate rains occur. Following these seasonal rains, these dormant juvenile parasites rehydrate and emerge from their galls. The parasites then migrate toward emerging grass seedlings. R. toxicus can adhere to the nematode cuticle and co-colonize the developing grass ovaries. The parasites complete their lifecycle by modifying developing plant ovaries into nematode galls. The bacteria, R. toxicus, can transform the modified seed gall into a toxigenic bacterial gall.

During colonization, R. toxicus produces neurotoxic tunicamycin-like ‘corynetoxins‘ that can cause disease in animals that graze on the infected plants. The toxins are tunicaminyluracil antibiotics, producing their effects through inhibition of protein glycosylation. They are referred to as antibiotics because they inhibit bacterial wall biosynthesis. However, they are also harmful to animals due to their inhibition of protein glycosylation.

The disease

The bacterial toxins produce a neurologic syndrome that is primarily categorized by dysfunction of vestibulocerebellar system. The syndrome mimics many of the clinical features of the staggers syndromes caused by tremorogenic mycotoxins, seen in perennial ryegrass staggers and dallisgrass poisoning. These initially include fine muscle tremors (fasciculations) of the shoulder, chest, and thoracic limbs. There is frequent blinking, ear twitching, head nodding, and muzzle tremors. The gait becomes abnormal, with jerky movements and a pronounced hypermetria. There is ataxia (without weakness) and truncal sway. This is an exaggerated, high-stepping gait found commonly on horses with cerebellar diseases. Animals in the early stages of the disease are often bright and alert, and continue to have a good appetite. The signs are exacerbated by excitement and blind-folding. As the disease progresses the animals become recumbent and develop convulsions before death.

Diagnosis of ARGT

Feed can be examined grossly for the presence of ryegrass seeds with parasite and bacterial galls using a light box.

The test currently performed on feed samples is an ELISA for the bacteria. There is an ELISA that can quantify the bacterial toxins, but it is more expensive and takes longer to complete. The results are reported as bacterial galls per kilogram of feed. The main problem is that bacterial seed head galls may be variable in both pasture and hay samples. It is recommended that 15% or 12 bales of hay bales should be sampled (whatever number is the largest). Methods for collecting samples are well described at the WA Department of Agriculture website. Hay bales are sampled using a hay bale corer. It is recommended to obtain 100 grams from each of 10 bales for one 1 kg sample. Current cost is $66.50 per kg sample. The results provide a risk rating for potential toxicity. The hay vendor should provide a declaration stating that the hay has been tested and is safe for livestock consumption. Intestinal contents or faeces can also be tested from deceased animals.

Treatment

There is no effective treatment for ARGT in horses. Animals should be removed from potential sources including pasture and hay immediately and feed a known negative feed source. Nasogastric intubation and delivery of mineral oil or activated charcoal are theoretically useful. If chemical restraint is required consider using diazepam (50 mg slow IV per 450 kg). Slow infusion of 10 gm of magnesium sulphate may provide temporary relief of signs.

Prognosis

The prognosis is typically guarded to poor for clinically affected horses. It is however recognized that horses may present with relatively mild signs with a good outcome. Signs frequently continue to worsen for days after removal from the source. This is related to previously ingested toxins within the gastrointestinal tract.

Prevention

Prevention is achieved primarily achieved by acquiring hay that has been tested prior to sale. Unfortunately the limitations of testing are such that this cannot 100% guarantee that the hay is safe. There are a number of strategies that hay growers can use to control ARGT, including using the twist fungus Dilophospora alopecuri to reduce nematode and bacterial numbers.