The term ‘choke‘ is used to describe horses that have an obstruction of their oesophagus, the section of the digestive tract that connects the mouth and the stomach. There are several substances that are commonly associated with obstruction of the oesophagus in horses. These include hay, pellets or cubes, foreign bodies (e.g., apples, potatoes), bedding and medicinal boluses. The problem often occurs when a horse rapidly eats hay or pellets without adequate chewing. This is accentuated in horses that have recently exercised or travelled due to dehydration. Choke can also be a consequence of a heavily sedated horse given access to feed too soon. If feeds that swell when moistened are inadequately prepared they may pose a risk for oesophageal obstruction. This includes beet pulp products, such as Speedi-Beet.

There are less common causes of choke, including oesophageal diverticulum, intramural oesophageal cyst, tumour or abscess, or a stricture from prior oesophageal injury. Geriatric horses are predisposed to choke due to poor dentition and decreased saliva production. Friesians can have a variety of upper GI problems including megaoesophagus, chronic choke, and delayed gastric emptying.

Most obstructions occur proximally in the oesophagus, close to the oesophageal opening. Less commonly the obstruction may occur distally, at the thoracic inlet.

Signs of choke

Affected horses can have a range of signs, some of which are related to the length of time that the choke has been present. Unlike cows, horses do not develop dilation of the stomach with oesophageal obstruction. Eructation is an important and necessary part of the digestion process in ruminants.

Early signs of choke include distress and anxiety, they may retch, and have their head and neck extended. They will salivate excessively, with saliva present at the nose and mouth. The discharge from the nares will often contain feed particles. If the signs persist for more than a few hours the horse may become depressed and dehydrated. The obstruction may be obvious to the eye in the proximal oesophagus.

Saliva and feed particles at the nares

Management of choke

Most cases of choke resolve spontaneously. It is not uncommon for vets to arrive and pass a nasogastric tube into the stomach without resistance. The diagnosis and treatment of choke occur simultaneously. The nasogastric (stomach) tube is passed until the obstruction is reached, simple obstructions are often resolved with gentle manipulation and pressure on the tube. If flushing is to be attempted the horse must be sedated such that the head is lowered, reducing the chance of fluid and feed being aspirated into the trachea. Flushing is achieved by simultaneously pumping water and applying gentle backwards and forward pressure on the tube. If the obstruction doesn’t resolve it is often prudent to wait 12 hours to see if the horse can spontaneously resolve the obstruction.

If on return the obstruction cannot be relieved then referral to a hospital facility becomes necessary.

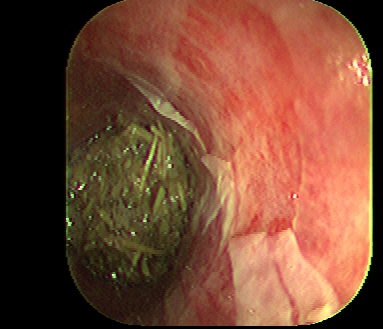

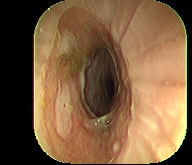

Assuming that the choke has resolved it is wise to pass an endoscope to examine the mucosal surface of the oesophagus. Withholding of feed for 24 hours is often indicated, followed by feeding of a soft cruel based on soaked pellets. Typically resumption of a normal diet can resume in 7-14 days.

Complications are numerous, many of which are serious and potentially life-threatening. These include perforation of the oesophagus, aspiration pneumonia, and oesophageal stricture.

Tags: Gastrointestinal diseases