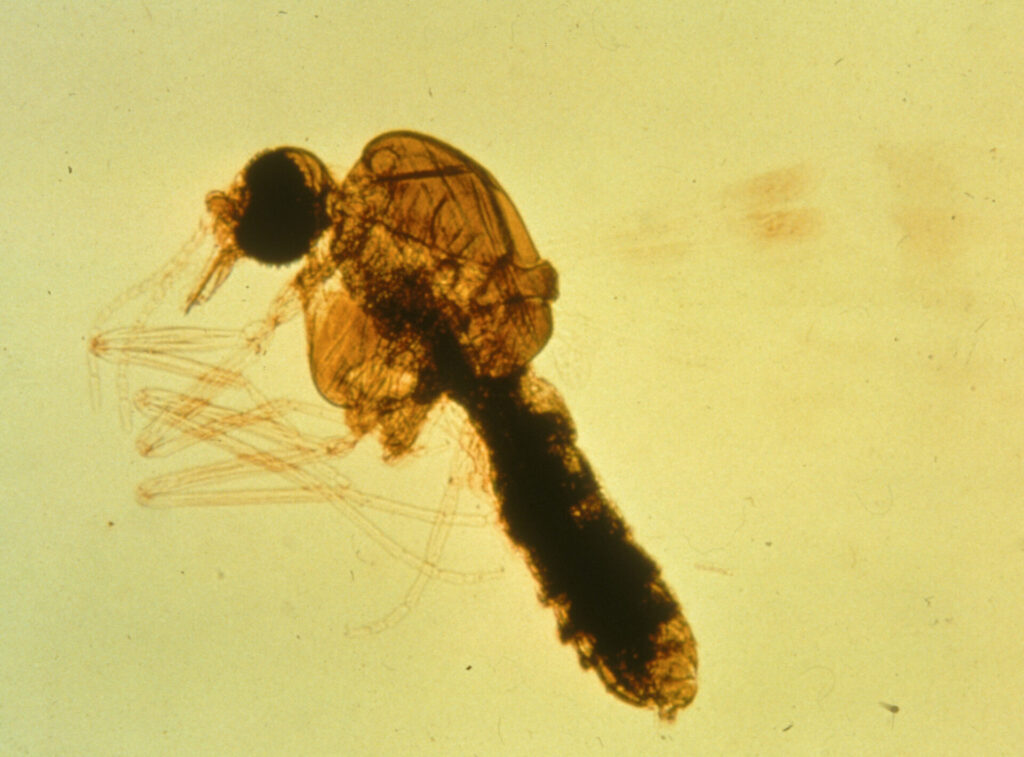

Culicoides hypersensitivity is described by numerous terms including Queensland itch, summer itch, summer eczema, or sweet itch (in the UK). There are many Culicoides species and they are best known as biting midges. They have piercing and sucking mouthparts. Their preferred time of feeding is at dawn and dusk and they are considered to be ‘weak’ fliers.

As the title indicates a bite by a Culicoides midge can induce a hypersensitivity reaction in horses. This is thought to involve both type I and IV hypersensitivity reactions.

The midges are also involved in transmission of the horse parasite Onchocerca cervicalis, a filariid nematode that has become rare after the introduction of ivermectin in the 1980s. This is most often associated with ventral feeding species of Culicoides.

Signs

The signs are induced hypersensitivity reactions, therefore the disease will always be sporadic. Affected animals are typically adult (>12 months of age) and there are no known sex or breed predilections. The lesions begin in the spring, are at their worst in summer, and disappear in autumn. The life cycle of the midge requires water, manure or decaying vegetation.

Signs can include three distinct presentations, pruritis, urticaria, or eosinophilic granulomas. Typically, the first sign is pruritis. This is followed by hair loss (alopecia), thickened skin, and excoriations (scaling, crusting). The lesions are commonly over the dorsum, base of tail, rump, back, withers, crest, poll and ears. This is commonly associated with dorsum feeding Culicoides brevitarsus, seen in Queensland and northern NSW.

Some horses will develop lesions on the head, neck, chest or ventral midline and again, this varies with location. This is the distribution commonly seen in Western Australia, almost certainly due to different species of Culicoides. This distribution can mimic that of onchocerciasis. Consequently, the distribution of lesions tend vary with geographic location. The signs typically worsen in succeeding years and the duration of signs tends to lengthen, such that some horses are affected year round.

Diagnosis

Often the diagnosis is strongly suspected on the basis of the signs and history. Biopsies typically reveal eosinophilic and lymphocytic perivascular dermatitis, consistent with an allergic response, although this could be consistent with other diseases. The classical differential diagnosis in cutaneous onchocerciasis, caused the larvae of Onchocerca cervicalis. Onchocerciasis is typically seen in mature horses (>4 years of age), is worse in summer but can occur all year round, may or may not be pruritic, and it rarely affects the tail. An approach to separating Culicoides hypersensitivty from onchocerciasis, as per Professor John Bolton of Murdoch University, is to give horses a long acting corticosteroid and ivermectin. If the pruritis returns in 3-4 weeks it is likely Culicoides hypersensitivity, if freedom from pruritis persists longer then onchocerciasis is likely.

Management

The key to management is to decrease the likelihood of the horse being bitten. This includes stabling at dawn and dusk using fine mesh to screen from insects. Some people paint the mesh with long lasting insecticide and/or use insect misters. Horses can be relocated to a high and dry environment to limit exposure.

Insecticides and insect repellents can be applied to the horse in later afternoon. It is recommended to use products that have 2% permethrin. Some products contain permethrin, DEET, N octyl bicycloheptene dicarboximide and piperonyl butoxide such as Flyaway (Virbac). Fenvalerate (0.5%) spray can be applied weekly (Sumifly – may no longer be available). Topical neem oil (1%) can be used as a repellent if the owner is concerned about using chemicals.

The pruritis is controlled through use of corticosteroids. These can be used systemically or topically. Daily use of prednisolone (2.2 mg/kg) or longer-acting parenteral corticosteroids can resolve the itching, but will return when drug loses activity with time.

Tags: Dermatology